Original publication: July 1977.

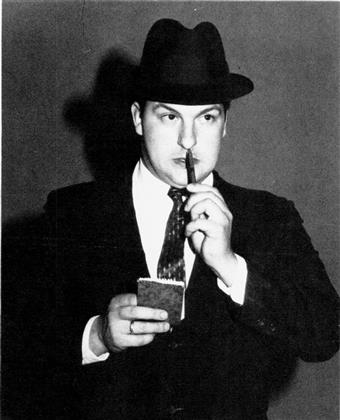

Thank you for reading this post, don't forget to subscribe!A TOP NARC

The Care and Feeding of Informants by Paul Krassner

Narcs are everywhere. Little is known about their methods because narcs don’t talk about their work, which consists of making other people talk to them. For some reason, a senior narcotics officer recently decided to tell it all to High Times. Of course, it wouldn’t be worth his pension to tell you his name, but as the following interview demonstrates, he is a narc of vast experience with a detailed knowledge of the techniques police are using to bust someone this very minute.

He knows everything there is to know about infiltrating dealing scenes, busting dopers, coercing the cooperation of potential informants and keeping them coerced. He understands why people will betray their closest friends and even relatives, and he knows the precise moment when an informant becomes an ex-informer. After reading the interview, you will know everything he knows. Which may help protect you from being busted.

As the narc talks, it soon becomes clear that he and his colleagues have made the first important breakthroughs in “informant management control and utilization” since the days of Judas Iscariot. They sort of built a better mousetrap to catch a better mouse—the dope “kingpin.”

Modern narcs work parallel or work up—that is, use the informant either to eliminate rival dealers at their own level or to arrest their own higher-ups. Virtually infallible methods of legal, psychological, and financial leverage are used to keep the informant in line. Narcs are powerless to control people who have nothing to gain by selling out. This interview shows why.

High Times: I’d like to discuss with you the care and feeding of informers. People in my circles look down on them, of course, but in all the drug and police literature I’ve seen there doesn’t seem to be anything about informers from your point of view.

Narc: That’s true. You can read the old Plainclothesman, which has been kind of a handbook for the last 55 years on undercover police work, but nobody’s ever talked about informants—what I like to call management control and utilization of informants. The attitude has been, we work with ’em, we know they’re there, but let’s bury our heads in the sand and not talk about them. However, I think that’s a mistake. We should be talking about informants. They can be treacherous. I say “treacherous” only in reference to narcotics informants.

High Times: Why are they different from other kinds of informants?

Narc: Well, I’ve worked varied assignments, from burglary to robbery to homicide. But what makes narcotics so different is that it’s the one area where the informant is actively involved in the crime you’re investigating. He’s a user or he’s a dealer himself.

I doubt very much that they inform because they’re good guys. They inform because they’re working off a case. That’s the primary reason a narcotic informant works for us. He’s working off a rap that we’ve got him on.

High Times: What about just plain greed?

Narc: Oh, sure, we’ve still got the mercenaries, and they’ll do it strictly for hire. Enforcement agencies don’t all have the funds we’d like to have to work more like this, but those informants work for money.

Also for revenge—a very common reason to get a narcotics informant. They’re mad at somebody. A guy ripped them off. Gave them some bad stuff. Stole their money. So it’s revenge.

We have to be aware of the motivation. If we’re gonna sit down and analyze a narcotics case based upon informant information, then we ought to know what motivates the guy to come to you in the first place and give you that information.

High Times: Is the motive ever to get rid of competitive dealers?

Narc: Yes, definitely. I really believe that this is an area we don’t pay attention to too much, but it’s very important. Eliminating the competition is definitely a motive in narcotic informants.

High Times: O.K., let’s get back to “treacherous.” How do you mean?

Narc: Well, just look at the dangers informants impose on a police agency. Historically, our society has always been for the underdog. Americans are like that—rahrah for the underdog! The utilization of informants by the police, by and large, is still thought to be extremely repugnant in the eyes of the general public. I’ve got city councilmen in Los Angeles who tell me police should never use informants.

These people are unrealistic. They’re not aware of the problems, of the search and seizure restrictions, of the law restrictions on police work—especially in narcotics. They can’t understand why we can’t make a case without informants.

It’s just a fact. In most cases we can’t operate unless we have informant cooperation, but to the general public it’s a repugnant area.

High Times: What are the specific dangers informants pose for you?

Narc: Double-dealing. I’ve never been associated with any facet of police work where there were more double-dealers than with narcotics informants. They are the worst people that I can imagine. What’s important about recognizing that is that you’re going to place an undercover officer in jeopardy if you don’t maintain the kind of control that a narcotics informant deserves. You’re playing with the lives of cops out there, and cops’ lives should never become secondary to a good narcotics case. If you can’t control that informant, you’ll lose that officer.

You’ve also got a lot of money out there. With all these federal grants coming in, it’s nothing to go into the field any more with hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Beware of that informant. He’s a double-dealer. You’ve got to watch him close to protect your interests.

High Times: Don’t cops sometimes become personal friends with informants?

Narc: Worse. I’ve found that with narcotics officers there is a tendency to initiate this friendship with an informant. You know, they’re coming over to the house to have dinner with the family on weekends.

Narcotics cases never go off on time. You’re going to be there two, three and sometimes four days. So now we place this young undercover officer in a room with this informant, and they’re sharing everything together for four days. They’re drinking, they’re eating, and they start developing a friendship.

Pretty soon the dope pusher shows up, and they get into a real tight squeeze, and that informant just comes through and verbally rescues him. He saves the day. And the officer will come up to me and say, “He’s a great guy!”

When you try to chastise the informant, the officer will say, “Gee, Cap, you know, he’s good people. He really bailed me out of that motel room.” Well, that’s a bunch of bull. He didn’t bail that officer out. He bailed himself out. You know, if the officer gets hurt, it’s the informant.

He’s got another thing at stake. He doesn’t want the thing to get burned, because then the pushers will know that he’s working with the cops.

And, third, if he’s working off a case, he wants the case to go down—and, if he’s working for money, he needs the bread. So his interests are self-serving. But you try convincing a young officer of that when he has just developed this life-long friendship with an asshole. It’s just that simple, because that’s what they are, every single one of ’em.

High Times: Do you actually warn your officers against becoming friends with their informants?

Narc: I plead with them, don’t develop this type of attachment. You have to treat them nice, but you do it in a business relationship.

We’ve got to keep our objectives in mind. You can’t fall trap to developing personal friendships, because if an officer gets into too much personal involvement, he starts losing his objectivity. He just doesn’t function any more. You can recognize this—this officer will come to you every time with information and say, “This is it! It’s the French Connection!” Every case is the French Connection. Actually, it’s only half a lid in a parking lot somewhere.

Officers must beware of personal and emotional involvement. At the same time, all informants must be known to management. This is a cardinal rule. Probably the most controversial criterion among all police officers. I used to be a field investigator working vice and narcotics, and that informant was my bread and butter.

When rating report time comes, what am I being rated on? I’m being rated on my performance. I’m being rated on my output and the quality of my cases, and in narcotics probably 85 percent of your cases are based on that informant’s information. I don’t want anybody else knowing about him. He is nobody’s business but mine.

But in order to protect itself and to protect individual officers, the department must know the identification of every informant. Put yourself in my position when I was in Narcotics. I had 82 investigators working in the field for me. If I don’t know the identification of an informant, then how can I make an intelligent decision as to credibility?

And there’s the matter of priority. Narcotics cases are all the same. You can have five squads or a hundred squads: they’ll all work out there for two weeks, and all the cases will break at the same hour—it never fails. All right, the supervisor, the OIC [Officer in Charge], the captain, he’s got to make the decision as to which case gets the priority. Which guy gets the manpower, which guy gets the bust, which guy gets the equipment. How can I make that decision if I don’t even know who the informant is?

High Times: But aren’t you holding their own cases over their head?

Narc: Absolutely. This is the part that really amazes me. How can I agree to tell a guy we busted for the sale of a couple of ounces of heroin, “Yeah, we’re gonna let you cop out to straight possession, and we’re gonna recommend no jail time and a couple years of probation,” if I don’t even know who I’m talking to?

How can I decide how much money I’m going to pay an informant in a case if I don’t know who I’m talking to?

And if something goes wrong—a dead officer in a motel room, and I have to go see the chief and he asks who the informant was. I have to say, “I don’t know, Chief.” How do you pin the responsibility when something like that happens if the only guy who knows about the informant is dead? Somebody in a supervisory or higher role should know the identity of all informants.

Keep in mind that when I talk about the character of a narcotics informant, I’m talking on a minus scale. It’s relative; some informants have a more negative character than others. That has to be weighed when you’re making a decision about working a case. How can I do that unless I know the identification?

High Times: When you say the identity, to what extent do you mean?

Narc: Good question. What good is knowing his I.D. if you don’t have pertinent information? When I first went to Narcotics, we had informant files, 9-by-ll cards they used to call vice-intelligence cards. If I was lucky, and most of the time I was not, there was a picture, a mug shot, in the left-hand corner. It also contained information like: Name—John Smith. Description-Male Caucasian. Hangouts— Hollywood. That’s wonderful, that’s really wonderful. I’ve reduced it now to about 800,000 people if I want to look for him.

So, I was dissatisfied and devised my own file. It’s nothing fancy: I got an orange package together that includes certain things I felt I had to know in order to manage that unit effectively.

High Times: Such as?

Narc: Such as CII [Criminal Intelligence and Identification] rap sheet—that’s available to everyone in the unit, and I’ve never met an informant who didn’t have a rap sheet. But what interesting things a rap sheet tells you when you start talking about a future case.

A guy comes in and says, “I can do a guy who’s going to sell you 30 kilos of pure heroin.” And you look at his rap sheet and he’s got five baggie arrests and a drunk arrest. Maybe he can still make the case, but it’s going to make me wonder whether this guy has moved in the right circles to come up with that kind of information.

Now, if he’s got some pretty heavy stuff in his package, that’s one more on the plus side which may lead me to believe this guy. But it’s just one more factor that I need to make that kind of decision.

A good mug shot. Everybody’s got one. It sure would be nice to have a picture in the package in case the guy splits with your bucks out in the field or somebody gets hurt and we don’t have to send to Sacramento and wait three days for a package to come back with a mug. You’ve got it, you duplicate it, you pass it out there it is.

And fingerprints. Everyone’s got prints if they’ve been arrested. Why not put it in the package? Maybe when that guy goes in on a controlled buy and swears up and down that the seller gave it to him, and you take the prints off the cellophane bag, you find that the informant’s prints are the only ones there. You find out if it’s a setup. Just one extra little thing, and I’d like to know about it.

I’m talking about a complete personal history. I want to know about his family, I want to know about his hangouts, I want to know his welfare number, I want to know his union number, I want to know his previous occupation, I want to know where his kids go to school.

High Times: Why would you want to know that kind of stuff?

Narc: Well, you need to keep in mind that today’s informants are tomorrow’s suspects. If we’re going to catch him someday, what a more beautiful opportunity to get all the personal data in his package then when he’s working for you and he’s talking to you.

I’d like a chronological list of contacts. I don’t want arrest reports. I can go to the file and get that. But I’d like to know what happens every time we go out with this guy. So I invented a little Mickey Mouse form that tells me date and time, the number of the case and how much we paid him. As a manager, I like to keep track of how much we paid a guy. If I’m paying a guy ten dollars a case for two years, and an officer comes in and says, “I want a thousand dollars for this one,” I’d like to ask, “Why? What makes this so special?”

One of the good things about this chronological list of contacts from the managerial side is that you can see when a guy’s been out 20 times and scored 18 of those times. You’ll think, “Now, that’s a pretty good percentage, and this guy’s pretty reliable.” So when that officer comes to me with a case in the future based on information from this informant, he’s going to get a lot more consideration than someone else.

It’s also nice to know about negative contacts, though. How many times have you been out with the guy and you didn’t score? I’d like to know if we’re wasting our time with an idiot who’s not producing at all. But I don’t know a way to get police officers to give me the negative contacts. They don’t want to lose the guy.

The officers also grow to like the package, because when they go to court and fill out that affidavit about the reliability of the informant, they don’t have to take out 20,000 pieces of paper from their desk and go back to see how many cases he turned and how many were convicted—it’s all right in the package. They can just look at the package, and they’ve got all of the information at their fingertips.

High Times: Before when you said something about the informant having some pretty heavy stuff in his package, I didn’t realize you were talking about his rap sheet; I thought you were talking about the actual drugs seized upon arrest.

Narc: Oh, no, I tend to put down seizures.

I must confess I am not seizure-oriented. I think about a year ago we kind of polled everybody in southern California as to an estimate of how much narcotics you really think law enforcement confiscates off the streets, and I think, at the maximum, we said five percent.

Other departments are like mine: we put out fantastic press releases saying that last year we confiscated $86-million worth of narcotics off the streets of Los Angeles. I’m just afraid that some day a reporter like you is going to multiply that by 95 and tell us how much we missed.

But seizures don’t mean anything to me. I’d rather get the boss of a narcotics organization with a bundle in his shirt pocket than I would get his mule with about ten kilos. Because we’re never gonna clean this stuff up—not until the Mexican government wants to clean it up.

And until they make up their minds, we’re just gonna be picking up after them all the time. Still, we can start hitting the tops of these organizations, and I think that should be our goal.

There’s one way to get no cooperation from investigators. That’s to require them to give you their informants openly in a file form, so anyone who walks in the room can inspect it. That’s not the way to treat a police office.

This is a confidential thing, and if you don’t understand the relationship between your investigator and an informant, then you’re in the wrong field, because that’s more than a case number; it’s a matter of personal rapport. So there has to be limited access. It should go into one man and then you can communicate by a preassigned number. We use the officer’s serial number, and then his informants are listed A, B, C, D, E and so forth.

Now we don’t put it on an arrest report: “We received information from #11685B.” That’s a pretty good tip-off that you have an informant file. Keep it off of arrest reports. When I used to get the reports on the update of the file, I didn’t care what they wrote it on. The back of an envelope: “Last night we went out with #114A and he turned three arrests and we got eight ounces of heroin.” Put it in a sealed envelope and drop it on my desk.

It’s not that much work to upkeep it. I found that once you start it the officers want to update it, because they want their informants to be looked upon by you in a favorable light for future consideration. So, if you’re going to start a file, keep it secret and have a way you can communicate with your officers.

High Times: Could those files be subpoenaed in a drug trial?

Narc: Well, I tried to find an appellate case that required the disclosure of such a file, and I have not found any yet. There was a sergeant back in Washington, or Baltimore, that went to jail for three days for contempt of court, but he got out. That was his decision to make. You don’t mention it on any reports, and I think when you deal with informants, it’s the same as when you go to court now and the judge demands you reveal the informant.

Your option is to say no, and they dismiss the case. It’s as simple as that. I made my decision personally—having a cabinet with about 300 informant packages—that there was no way I was going to surrender that to a court. I’m not going to be responsible for that many executions.

High Times: I’ve heard the expressions working down and working parallel. Could you explain those methods of working with informants?

Narc: This has always been a sore spot for me, and I think it’s a danger you impose on every police agency when you work a narcotics case. Working parallel is essentially when a guy that you busted is going to trade and give you five or six for one. What he’s actually doing is eliminating the competition. I have no great objection to this, but we ought to be aware of what he’s doing.

The informant that works down is the guy who’s up there in an organization, trading you guys who are lower down. If you accept that kind of a trade, then you have committed an unpardonable sin as far as I’m concerned. This is the guy that you bust and say, “If you cooperate, we’ll let you go,” and he says, “Great, I’ll give you six arrests.”

If you’re the type of agency or officer that is so impressed with quantitative results of narcotics investigations, you’ll bite at it. You’re dealing with a guy who’s selling out his customers to get off the hook, and if you allow that to happen, then you’re being remiss in your responsibilities as a narcotics officer.

You never go down with an informant. You always go up. If he can’t take you up, good-by—he goes to jail. It’s that simple.

High Times: You said before that working parallel is the same as an informant eliminating the competition and that you didn’t object to that. But isn’t the informant then exploiting you for his own selfish goals?

Narc: So the guy wants to knock out all the same-level pushers in town—that’s not so bad. You follow him around and you do it. Fine. Just remember to get back to your informant when you finish with the others, because what you’re doing is giving him a monopoly in your city. He’s knocking out everyone else under the guise of being your informant, and he gets bigger and bigger. An officer should be aware of that.

Ideally, you point the informant in the direction you want to go, not where he wants to go. There are times when you know that John Smith can get right in to the John Jones Organization, who you’ve been trying to bust for five years.

The informant says, “I’ll give you three other organizations—three for one.” Don’t let him do that to you. Say, “No, here’s where I want to go and here’s where you’re going to make your buy.” And if he’s got a case on him, he’ll eventually have to do it. There’s no question about it.

But if you start following informants around town, it’s kind of like the shotgun approach. They become squad leaders and case leaders, and you’re running around after them all the time. The best way to do police work is for the police officer to give the direction to the informant and then send him out hustling.

Beware of an informant who has a tendency to build a minor case into a big case. I am convinced that a lot more big pushers in California are created by us.

High Times: Could you expand on that?

Narc: I’ll tell you what we do. The informant snitched us in, and this guy is used to dealing bags of heroin, and we take him in the motel room and say, “Hey, buddy, you wanna see a hundred thousand?”— and we flash the money. His eyes open wide and he hangs us up for two days, because for the next two days he’s going all over the county trying to round up enough dope to sell to you. I think if we ever did a qualitative analysis on some of these cases, we’d find about 50 different degrees of quality.

Now we have created this monster. We’ve taken a little street pusher, waved a hundred thousand dollars in front of him, let him stall us for three days, he’s run all over, scored from as many people as he can, and then we bust him and we say in the newspapers, “Big Dope Pusher Nabbed by Cops!”

Is he really a dope pusher, or did we create a dope pusher? You’ve got to be careful of an informant like that.

You also have to emphasize to an informant that as long as he works for you he can no longer deal. Now you know that’s a bunch of bull, and I know that’s a bunch of bull, because he’s going to deal. That’s the way he makes his living. That’s not important though. The important thing is that you put your agency on record as telling this guy that he does not get immunity just because he happens to be an informant, and if someone comes along and wants to bust him, more power to them.

I’m a firm believer that a good informant goes to jail once every two years anyway. It makes them better informants. High Times: Are you serious about that?

Narc: Oh, sure, but don’t misunderstand. I would not expect individual officers to arrest their own informants. I would tell someone else to do it. But what’s wrong with putting them in jail? It spurs them on to greater heights. But you cannot give them immunity. There’s no way that you can promise a guy that he has carte blanche license to deal in your town just because he’s an informant. You’ve got to go out front and make that point.

When you deal with a narcotics informant, each case must be properly planned. The one thing you have to avoid is that last-minute phone call when the guys calls you up and says, “It’s all set up. The case is gonna go down. It’s down in Malibu and it’s going at 5:00.” You look at your watch and it’s 4:05 and you can’t possibly get to Malibu until about 4:55 and the case is gonna go in 5 minutes. Don’t be trapped into that kind of situation.

Narcotics officers, bless their hearts, are the most zealous, most motivated policemen I have ever been associated with. They will run to Dallas by themselves to make a narcotics case if it looks good. But that’s where the sergeant comes in. You’ve got to sit back and say, “Wait a minute, we haven’t had time to plan this. We may not have sufficient manpower available. We don’t know where the hell we’re going. If it’s a motel, we don’t know where the room is, we haven’t got the rooms on both sides, we don’t know where the exits and entrances are, we can’t cover it, we can’t wire the room, we can’t wire the officer.

That’s what a last-minute phone call does for you. It takes away all the control you could possibly have. If you allow yourself to get sucked into something like that, you’re going to get a cop killed, and then you’re going to regret it for the rest of your life. You cannot plan a good narcotics case in 15 minutes or an hour. It takes hours of pre-scouting and pre-planning before you should ever go into those things. Officers should not fall for an informant that is always pulling a last-minute phone call.

You’ve got to make sure you know everything the informant knows. They’re all the same. They want that money you’re going to pay them or they want to work off that case, so they come in and say, “It’s all set up. The guy’s in there and he’s got two kilos of good cocaine. All you have to do is walk in and grab him. Just make the buy.”

He doesn’t tell you about the Doberman pinscher. He does not tell you about the guy in the closet with the shotgun. They have a tendency to forget to tell you all the negative things, because they don’t want to sour you on the case. They want it to go.

So you have to pump them for it. You can’t just accept that what the informant tells us is all there is to know about a case. Find out everything—positive and negative—and then make your own decision.

I remember my first week in Narcotics as a captain. I didn’t know anyone, a few guys, maybe, and I walked into the squad room and there must have been 70 guys in there from a whole bunch of different agencies. It was obvious that a big caper was going down, and I saw this great big guy with a beard and a lot of hair at the blackboard.

He had what looked like a picture of a motel on it and he said, “Here’s the room and the room next door. You wire the guy here and you cover this exit.” I stood back and thought, “Damn, there’s a sergeant. There’s a supervisor of the future.” And then I found out he was the informant. I could not believe it. This guy was running the case.

I tell my officers, you run the case. If your informant wants to be a cop, point him out to Civil Service and let him go through the procedure like everyone else. But, he can work under less restrictions than you can—like the law, ethics—such things don’t make any difference to him. They can’t understand why we can’t make cases sometimes. Don’t let him get that involved in a case.

I really hardened up in the end in my attitude about this thing. I don’t even like informants in the room during a briefing, to tell the truth. Let them get too close and they know your operation too well. Kick ’em out of the room. If you have a question, call them in, ask them, kick ’em out again. Don’t let them become squad leaders. That’s not their function.

High Times: But at the same time, aren’t officers trying to butter up informants?

Narc: That’s right. That’s why we have to provide for sufficient manpower and equipment, so as not to depend totally on informants’ needs. If you haven’t got enough people to cover a case adequately, call it off. We seem never to want to call anything off. If it wasn’t for the fact that a squad leader or a lieutenant had enough guts to say, “Let’s go home,” I suspect some of my troops in Narcotics would still be on the Mexican border two years later waiting for that guy to come across. What’s wrong with hanging them up once in a while?

Sometimes I think we give ourselves away. What other buyer do you know of that when the pusher calls at three o’clock in the morning and says, “We’re ready to go; do you have the $400,000?”— what other buyer replies, “I got it, I’ll be there”?

You don’t walk around your house with a couple hundred thousand dollars. What’s wrong with telling the guy, “Hey, I can’t get my bucks together that fast. Let’s make it tomorrow afternoon. You caught me by surprise.” Why put yourself at the disadvantage of having to run out there when you don’t have enough manpower or equipment?

If you’ve got a lot of money in a motel room, you can’t cover that thing with three, or even five, guys. You’ve got your operator, you’re going to have to wire the room, have people next door; you’ve got guys in the lobby, you’ve got guys outside. If you don’t go through these painstaking things, you’ll wind up with a dead or injured policeman, and there’s no narcotics pusher who’s worth that sacrifice.

I always say, don’t become so idealistic that you think your bust will end the narcotics addiction problem in California. It’s never going to happen. You do the best you can, but you don’t do it at the risk of the life of an officer. If you can’t plan properly, if you don’t have the right equipment, if you don’t have enough officers, call it off or hang it up.

High Times: On a pragmatic basis, how do you actually deal with the treachery of informants?

Narc: Well, if you’ve got an informant that’s going in on a controlled buy, search him before he goes in. Make sure, for court purposes, that he’s not carrying the stuff in and then carrying it out and saying he bought it. Wire the informant whenever possible.

I know that a lot of times you can’t put a wire on an officer, let alone an informant, because it gets too hairy, and sometimes we get shook down on the inside. But in most cases I’ve been on, my guys never get searched, so you can wire them.

I like wiring because you can sit outside, listen to the conversation and determine for yourself how the case is going. Then you don’t have to trust the informant’s word about the progress of the case. He’s got an incentive. He’ll stall you while you sit with ten guys at time-and-a-half, and other cases need to be gotten to, and you waste your time just because you’re forced to rely on this idiot’s word.

So, if you can get away with it, wire him. If you can hear him, you can make the decisions. Of course, if he’s dealing money for you, be sure and record the serial numbers. That’s kind of basic.

And here’s something that I find we forget to do on many occasions. You’ve got to ascertain from the start of the case whether the informant’s going to lay himself out in court or not. It’s a very simple question: Will he testify? But how many times do we forget to ask? How many times do we assume that the guy’s gonna testify in court, and then that day comes and he says, “Me, testify? You’ve got to be out of your gourds. You know these guys will kill me. I’m not getting up there on the stand.”

It’s very important. If he’ll testify, you’ve got an easy investigation. This guy goes in, he gets stiffed into the organization, issues a little signal, you make the bust, and that’s it. But if he won’t testify and you’ve got to protect his identification, you’ve got a different kind of investigation. Then you’ve got a lot of surveillance to do. You have to work around the informant.

High Times: But, to a certain extent, you have to let the informant in on your scenario, right?

Narc: Yes, but he must understand that he follows the script and that he does not have the right to make changes. What’s the sense of having a three-hour briefing with a hundred officers if the informant goes in and the guy says, “I don’t want to flash the money here. Drive down to Point Moogoo and on top of a tree we’ll do it up there.”

The guy says, “Yeah, yeah,” and you don’t know what’s happening. He takes off with the money and you’ve got 20,000 guys having traffic accidents trying to keep up.

The informant does not have that kind of authority. I don’t even like it when a police officer changes the script on sudden notice when nobody knows about it. There’s an easy out. Instead of the informant posing as the man, you tell him that he represents the man. So whenever these kind of changes come up, he says, “Hey, guy, I’ve got to get to a phone. I’ve gotta call the man. I gotta get approval before we can do this.” And then he contacts us and we can weigh the decision as to whether we want to do it or not. Too many rips go down because the script has been changed.

I don’t like moving money anyway. I never move money. The money stays in one place. You start moving it around and you’re gonna get ripped. You can’t keep up with it. It stays in a place that you can watch; that’s open to you, that you can hear what’s happening in the room, and you’ll never lose money that way.

High Times: Can we talk a bit about the actual arranging of deals with informants?

Narc: Well, this is a guy you’ve busted, and now he wants to deal with you. The most desired way, as far as I’m concerned, is money. The mercenary is the kind of guy that I like to deal with, because this eliminates that bad stigma we talked about—in society’s eyes—about letting a known dope pusher escape.

This guy is strictly doing it for the money. Unfortunately, all of us have funding problems and we can’t afford to play with these kinds of cases. We had one case that we went to San Antonio on with the federal authorities. It didn’t work out, but had it been successful, the informant fee was $34,000 for 110 pounds of coke. If you’re going to deal for money, then the approval has to come from the commanding officer or the OIC.

I think you have to assist officers. You’ve got to set some standards for them. For instance, you say, “O.K., on heroin cases, for every pound we’re going to go a hundred dollars”— or whatever your figure is. That’s to give them a basis to open up the discussion in the field, only because when you start determining how much a case is worth, don’t get hung up in seizures.

There are a lot of variables that have to be considered, such as what kind of a case is it going to be? Is this guy talking about some little street pusher or is he talking about giving us the boss of an organization? A boss is worth a lot more than a street pusher, so you’re going to have to pay more.

What’s the informant’s past record of accomplishments? You’re going to pay a guy who’s turned 20 straight cases a lot more money than a guy who’s there for the first time.

High Times: What would you say is the most important lesson you learned as a commander?

“We put out fantastic press releases saying that last year we confiscated $86million worth of narcotics. I’m just afraid that some day a reporter like you is going to multiply that by 95 and tell us how much we missed.”

Narc: In my 18 months as the commanding officer of the investigations section, I would say that the commanding officer has to give the final approval, because my experience has shown me that officers tend to be too generous.

Whenever an officer used to come to me, I felt like an Armenian rug merchant. He’d say, “We want to give the informant $500 for this case,” and I’d say $50, and he’d say $400—and we’d reach a point where I knew I was getting screwed anyway just by agreeing to it. But let’s face it, that’s that officer’s bread and butter. That’s his boy. He’s giving him all his cases. He wants to keep him happy, and by keeping him happy you give him as many bucks as you can.

But you’re the old supervisor now, and you’ve got a different role. You’ve got other people to keep happy, and you’ve got to disperse the funds evenly. Again, for this kind of assistance, you need some kind of files.

If you want to create animosity in your units, you start paying one guy $1,000 every case and you’ve been paying another guy $50—the same kind of case—and you watch the officers start in: “How come his informant gets more than mine?” You’ve got to be fair as a commander. That’s why I keep emphasizing: you’ve got to have a system.

No money, as far as I’m concerned, should ever be given to any informant until the case is finalized to your satisfaction. Give an informant the money up front and you take away his motivation. If you want to see an informant break his back to make a case, keep him hungry. He’ll kill himself if he needs the bread.

And, notice, I just said, “finalized to your satisfaction.” If you had a deal where to get the boss of an organization you’re going to pay $500, and then the informant comes in and the case is over but you wound up with a guy two places down from the boss, is that still worth $500? Not as far as I’m concerned. You had a verbal contract with this man and he didn’t deliver, so you prorate it. Maybe it’s worth $100 or $150, but don’t let them sucker you in by making a big promise for a lot of money and then compound that felony by paying them regardless of the outcome.

High Times: What about the informant who’s working off his own case?

Narc: Well, that’s the most common way of working with them. This is the guy you busted and now he wants to come in and make a deal with you. You’ve got to keep in mind, and you’ve got to remind all officers, that you cannot make a deal. A police officer is not empowered to do that. That’s the prerogative of the judiciary and the district attorney. The D.A. makes the decision to file and the judge makes the decision to convict. A police officer does not have that right. He merely promises to recommend. How many guys must have been embarrassed on the street because they promised an informant more than they could deliver?

As with money, it takes prior department approval before you can set that kind of a deal. Investigators, as far as I’m concerned, should not be allowed to make their own deals. I’ll tell you why. Every once in a while you’re gonna run into that really politically sensitive case.

The investigator—he’s a good narc—he sees this whole bunch of stuff on the table. All he can think of is, “This guy’s gonna turn three top-ranked dope pushers for me in return for letting him go.” But he’s not privy to some of the information that the rest of the staff is—such as the guy’s on probation for molesting the mayor’s daughter.

High Times: Is this an actual case or just hypothetical?

Narc: That’s an exaggerated case, but you want to see some political sparks? Just go get into one like that. Or maybe this guy is just so repugnant in his character that no department can afford to work with him in the first place.

Most officers don’t have that kind of information. They lead a kind of channeled life of investigation. They’re not worried about administration. This is a management function as to whether or not you’re going to allow a dope pusher to go free, and it’s got to be with department approval.

When you’ve got your spurs into a guy, this is when you really get the good trade-off. At least three. If the guy doesn’t want to do it, what’s his option? State prison. And then you ought to actively make sure that he goes to state prison, if that’s the kind of guy he is. If you’ve got your hooks into him good, though, if it’s a good sales case to an officer, don’t let him off the hook by conning you into an easy trade.

Whenever possible, you tell him the case you want. He’ll take you a lot of different places in a trade-off, but if you know he can score from some guy who’s been plaguing your community, that’s who you want. And they’ll come across. They don’t want to go to jail.

Another thing—we don’t let attorneys come to the meeting. I had one guy show up one time with his attorney and say, “I brought my attorney with me. We want to set up the deal.” What is that? You’re sitting down to negotiate for a new house or something? Attorneys are out. This is something between you and that informant, and I don’t want to get tied down with a bunch of legal jingle-jangle. Keep your hooks into him and don’t let him off.

I’m not talking about the guy you arrest for marks and it’s going to be a misdemeanor anyway, and right there on the spot you make your deal and it’s dismissed and he works for you. I’m talking about the guy you’ve got for a good sales or possession-for-sale case. This is the kind of guy that you don’t go out front for. You let him go through the criminal justice system. If anything, it will show his peers that he’s not a fink. You know: “I got to go to trial today. If I was a fink, I’d have the case dismissed.”

High Times: How do you feel about an informant being set free and then going out and pushing again?

Narc: Well, I certainly don’t like to see a guy get off scot-free on a good case. If anything, he’s going to plead to something. If it was a good sales case, then we’re going to cop him out to a good possession case, and where you make the deal is on the sentence.

There’s no jail time, but you put the probation on him and, if you can, you put the terms of probation in there. Like they have in some counties—24 hours a day you will submit your bod and your car and your house to a search by any officer.

Keep in mind, two years from now this guy may not be working for you any more. He may be out there pushing, and if you’ve got that kind of information in your probation as a criteria of probation, what a beautiful way to go out and bust him. Don’t abuse it, is my attitude. Don’t roust people when they have that on their probation, but if you’ve got a good pusher, use it.

This may seem like a very minor point, but I don’t like police departments to go into court and ask for a continuance while the deal is going with the informant. Let me tell you why. Many police chiefs have been continually criticized for the delays in the criminal justice system. How many cases do we have that go two years before we even get to superior court?

Now, all of a sudden, we go in and request a continuance because the informant’s working for us. If the guy’s working for you and he wants to make a deal, he knows he’s going to get the charges reduced or not go to jail, so let the defense go in and ask for the continuance.

Then the people don’t have to object to it and, of course, we’re not going to. It’s a very small thing, but I think it would be kind of hypocritical to ask for a continuance and then scream about other cases where continuances are granted.

In most cases, I don’t believe you should ever interfere with the case until the sentencing portion. I want that informant to have on his record the fact that he has been found guilty of a felony violation. Again, we’re talking about the serious offenses. You’ve got him for sales and you’re allowing him to cop out to a straight possession with a promise of no jail time.

I want that on his record. I don’t want him to get the charges dismissed. I think you should show other law enforcement officials that the guy is up there in that kind of a circle. On the major cases, he’s going to have something on his record to indicate that he was convicted—not just charged—convicted, of a felony.

High Times: How does your department actually go about fixing these cases with the courts for a reduction of the charges?

Narc: An officer, first of all, is not allowed to go over and see the judge in his chambers to make a deal for the informant. If you allow the officer to go right into the judge’s chambers with no one’s knowledge—not consulting anyone—and make a deal with the judge, you’re defeating your purpose of control.

So, in our department, a letter goes from an assistant chief of police to the district attorney in which we request certain action be taken on a case, and that is relayed to the judge. The judges know—at least as far as Administrative Narcotics goes—that they don’t act on a case until they get that kind of letter coming through channels.

I think you have to set up that kind of a procedure for many reasons. First, management assumes its responsibility for controlling the disposition of serious felony cases. Secondly, it sure takes that police officer off the hook if something goes wrong. If you’ve got a captain, a deputy chief and an assistant chief’s approval signature on a letter of transmittal before the charges are reduced, it really takes the officer off the hook.

High Times: How do you go about handling questionable informants? Do you ever actually blackball them?

Narc: Yes, this has been one of the major liabilities suffered in law enforcement for many, many years. Let me give you some examples of the kind of guy I feel should be blackballed as an informant.

Number one is the guy who agrees to work for you and then, for whatever reasons—he’s chicken or he changes his mind—burns the operation in the middle of a case. This guy should never be allowed to work with any police officer ever again, because that informant doesn’t know what stage of the case you’re at. This guy could be directly responsible for one of your officers getting killed.

Number two, the guy who continually lies. He is always promising to make those big cases and he never delivers. You’re wasting your manpower, you’re wasting your equipment, you’re wasting your money. You should blackball him. Just forbid anybody from ever working with him again.

Number three is the guy who, in terms of long-range coordination, cooperation and effectiveness against narcotics problems, is probably the most dangerous of all. That’s the guy who plays one agency against another agency. This is the guy who goes to LAPD [Los Angeles Police Department] and says, “I’ve got a great case for you,” and you say, “Great, we’ll buy it.” Then he goes across the street to the sheriff’s and says, “I’ve got a great case for you”— it’s the same case—and they buy it.

We end up with two sets of investigators out in the field working the same case, wasting your time, and they may shoot each other out there because you all look like the suspects. You don’t know the players without a program. He’s the most dangerous individual I can find.

High Times: So is there actually a blacklist of bad informants?

Narc: Well, we’ve said, “All right, no one will ever work with that guy again.” But have we told the officers in our sister cities about it? Have we told the sheriff in our county about it? In the next county? No. We never did anything like that, and we allowed this individual to go from agency to agency to agency, up and down the state, wrecking good police officers’ careers, bringing down chiefs of police and wrecking departments. He should be blackballed out of the state. So I say, if we’ve got guys who are just no good, input them into that file.

High Times: What about informants who work on the other side of the border? Not a state border, but a national border.

Narc: I’ve done a flip-flop as far as my opinion on this problem goes. I used to let informants go to Mexico, and I was really convinced this was the way to make good cases. I must say in all honesty that I have changed my mind, and I feel there can only be one policy, which is that informants shall not go into Mexico while working as your agent.

When you think about it, you don’t have the right to tell a man that he has carte blanche to break the law in a foreign country. You can’t control his activities once he leaves this jurisdiction. He’ll tell you, “I’m just sneaking across the border to meet with the crooks to set the deal so that they’ll come back.”

Well, what happens most of the time is he goes across the border, sets up the deal for you and then says, “Well, while I’m down here, I think I’ll score for myself too.”

So he scores, and then he comes back across the border, and Customs grabs him and he’s holding. The first thing out of his ever-lovin’ mouth is, “I’m an agent for LAPD. I’m working on a case.” Well, I’m sure you didn’t have the kind of contract with him that he can go down and score for himself. It’s very embarrassing to have that kind of thing happen, and there’s only one solution to the problem: you have to tell him he can’t go. I don’t mean that you get him and say, “Don’t go to Mexico, please.” You’re giving him the ticket and the money. You’ve got to be emphatic. You’ve got to come out real strong and say, “You’re not acting as our agent if you go to Mexico.”

If we get an informant who’s going to insist on doing it, then call him on the phone and tell him he’s not going and then tape it. Then if he goes down there and gets busted, that’s tough luck as far as I’m concerned.

What are you gonna do if you tell a guy, “You will not act as my agent if you go to Mexico,” and he says, “Screw you, I’m going anyway.” What are you gonna do— kidnap him? Chain him to a bed? You can’t do that. He’s a free citizen. So he goes down there and you don’t hear from him for a while, and the next thing you know the phone rings and he says, “Hey, I’m back in San Diego and I’ve got five kilos of heroin with these idiots.” What are you going to do? You’ll bust him, that’s what you’re going to do.

You fulfilled your obligation. You told him not to go. He went. He’s a free citizen. Now he’s back in the United States and he’s got dope pushers with five kilos of heroin. Go down and bust him. But put your department out front on it. Don’t let this guy embarrass you by getting you into a situation where you have the State Department calling up asking how come we’re sending guys into a foreign country dealing dope. It’s an embarrassing thing for your department and for your chief.

Getting back to your question about blackballing, just because I put a name into a file as being undesirable, does that mean I cannot work with him? No. It’s not binding. There are times when you’re going to have to work with an undesirable informant. You take a case where an officer has been murdered, and the only person who can get to the killer happens to be a blackballed informant—you’d better believe you’re gonna work with him.

High Times: How would you sum up your point of view then?

Narc: If we don’t have some kind of system set up to control these informants, we’re going to lose somebody some day. I want my guys to think systems, think control, think devious when you’re dealing with a narcotics informant. If nothing else, you’re going to wind up saving the life of a cop. That’s my concern.

“I’m a firm believer that a good informant goes to jail once every two years anyway. It makes them better informants.”

The post From The Vault: Confessions of a Narc (1977) first appeared on High Times.